Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Population Health

Follow this topic

Addiction prescription

In Population Health

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

As Public Health England publishes the first ever review of dependence and withdrawal problems associated with five classes of common medicines, investigate the role that pharmacy teams can play in helping tackle these issues

From painkillers to antidepressants, we are lucky enough to live in a world with a whole range of medicines that play an important role in supporting the health and wellbeing of many patients – as long as they are prescribed and used properly.

In the midst of recent mass media and public attention on the issue of addiction to prescription drugs, Public Health England (PHE) has published the first evidence review of dependence and withdrawal problems associated with five commonly prescribed classes of medicines in England. The health body has also made recommendations for better monitoring, treatment and support for the people who take them.

Report findings

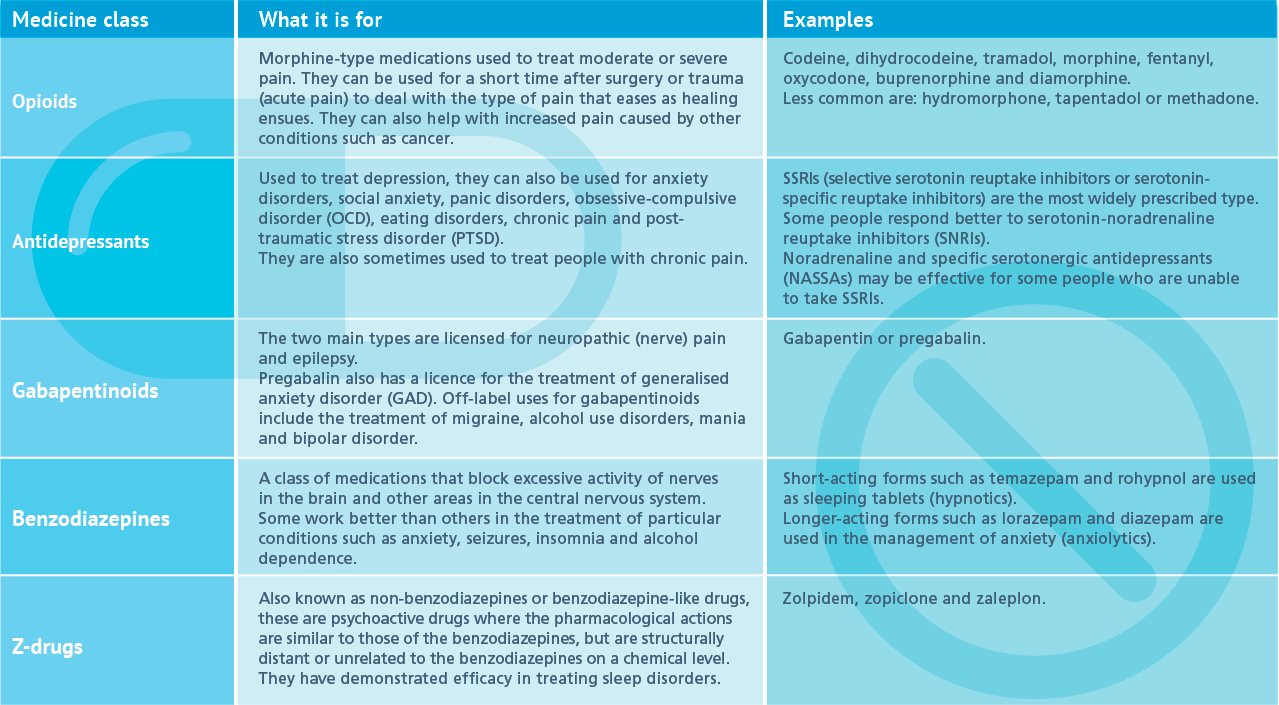

PHE’s Prescribed medicines review: report analysed available NHS prescriptions data from community pharmacies from April 2015 to March 2018 for five classes of prescribed medicines:

- Benzodiazepines (mainly prescribed for anxiety and insomnia)

- Z-drugs (insomnia)

- Gabapentinoids (neuropathic pain)

- Opioid pain medications (for chronic non-cancer pain such as low back pain and injury-related and degenerative joint disease)

- Antidepressants (depression).

Its findings were complex, and many patient groups were interlinked. For starters, the review found that in 2017/18, 11.5 million people – a quarter of all adults in England – were prescribed at least one medicine from the five classes.

To complicate matters further, PHE found that polypharmacy was common. About a fifth of patients (19.1 per cent) were taking two of the five classes of drugs, most commonly antidepressants and opioids (9.3 per cent of the total, about 513,000 people). One in 20 (5.2 per cent) received three classes, most commonly antidepressants, gabapentinoids and opioids (2.8 per cent of the total, about 157,000 people). Almost one in 100 (0.8 per cent) and one in 1,000 (0.1 per cent) took four and all five drug classes respectively, meaning some 48,000 people in England take four or all five of these classes of prescribed medicines.

When it comes to prescribing trends, the review found the number of prescriptions for antidepressants and gabapentinoids is rising. Between 2015/16 and 2017/18 the rate of prescribing for antidepressants increased from 15.8 per cent of the adult population to 16.6 per cent and for gabapentinoids from 2.9 per cent to 3.3 per cent.

Although the good news is that long-term prescribing of opioid pain medicines and benzodiazepines is falling, it still occurs too frequently to fall in line with the guidelines or evidence on effectiveness. And where some patients end up being prescribed these medicines for longer periods, it is likely to result in dependence or withdrawal problems.

Recommendations

No one is disputing that these drugs are vitally important for the health and wellbeing of many patients when prescribed properly, so the review makes a number of recommendations to tackle associated issues. It found patients felt there was a lack of information about medication risks and that doctors did not acknowledge or recognise withdrawal symptoms. With that in mind, PHE is calling for shared decision-making with patients and better information to be provided to patients about the benefits and risks of the drugs they are taking.

In addition, patients felt that their treatment was not reviewed sufficiently to monitor if it was working, so it is recommended that they should be encouraged to see their GP at least annually, but preferably every three or six months to review their progress.

Amongst other criticisms, some patients said they were not offered non-medicinal options, so PHE recommends that doctors should have clear discussions with patients and, where appropriate, offer alternatives such as social prescribing. Similarly, patients who want to stop using a medicine must be able to access appropriate medical advice and treatment, and must never be stigmatised.

Long-term prescribing

The length of time patients were taking these medications emerged as a particular concern.

Half had been on a prescription for at least 12 months, while between 22 and 32 per cent had been taking medicines for at least the previous three years. The issue here is that when used incorrectly, dependence and withdrawal from prescription medicines can be extremely difficult to cope with, often creating withdrawal symptoms similar, or worse, than the original condition they were prescribed to treat.

And if prescriptions are withdrawn, people can look to other sources to obtain their medicines. “An absence of support can mean that people turn to unregulated online websites to get the medicines they think they need without a prescription, which is highly dangerous”, warns Claire Anderson, chair of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

in England.

People who have been on these drugs for longer time periods should not stop taking their medication suddenly. If they are concerned, pharmacy teams can advise them to seek the support of their GP.

Deprivation, health inequalities and prescribing

Prescribing rates for opioid pain medicines and gabapentinoids have a strong association with deprivation, being higher in areas of greater deprivation. Prescribing rates for antidepressants, benzodiazepines and z-drugs are also higher in more deprived areas, although the correlation is less pronounced than is the case for opioids and gabapentinoids.

For all medicine classes the proportion of patients who had at least a year of prescriptions increases with higher deprivation, with those living in the most deprived areas being slightly more likely to be on a prescription for a year or more. The most notable difference in this proportion between the most and least deprived areas is seen in those prescribed gabapentinoids, 18 per cent versus 21 per cent.

There is still no clear reason for these links, but in 2018 researchers on a University College London study, Patterns of regional variation of opioid prescribing in primary care in England, suggested the workload pressures on GPs in poor areas with large numbers of sick patients could be one of the factors for high incidences of opioid prescribing.

The role of pharmacy

Community pharmacy teams can also be part of the solution for the millions of people across the UK grappling with prescription drug dependence and withdrawal.

Clare McKenny, senior pharmacist at charity Addaction, says pharmacy teams are ideally placed to advise patients of the benefits and risks before starting to take any new medicines. “Pharmacy teams can help patients in making more informed choices about their medicines, as well as providing ongoing support and advice to patients throughout their treatment journey,” she says. “They can supply broader advice to patients on a medicine, for example about its possible side effects or significant interaction with other medicines or alcohol. In particular, with the five categories of medicines researched, patients are probably not aware of the risks of addiction even with only short-term use.”

Pharmacy staff can also monitor patients over time. “You can intervene each time a patient receives a repeat prescription to check on how they are finding the treatment, whether they are experiencing any negative effects or have any concerns”, adds Clare, “as well monitoring the length of treatment and referring back to primary care clinicians if you feel this is not appropriate.”

Additional options

Although these medicines have their place, for some patients they may not be the best option.

Unfortunately the report notes that there isn’t enough evidence to draw robust conclusions about best practice for alternative options, although pharmacy staff can signpost people to services such as talking therapies, mental health support and social prescribing.

With a quarter of the population taking at least one of the five medicines classes, pharmacy teams have a crucial role to play in discussing and reviewing medicines with patients, as the problems of dependence and withdrawal become more well known.

Click on the table above to see a larger version.