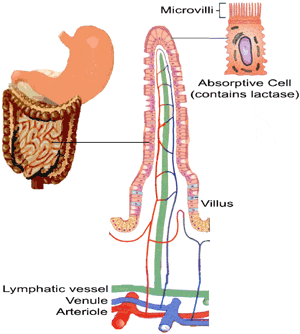

Lactose, a natural disaccharide, is the principle carbohydrate found in milk; it is a good source of energy and helps the body absorb minerals such as calcium and magnesium. Lactose is broken down in the gut into two monosaccharides, glucose and galactose, by the enzyme lactase. Lactase, also known as beta-galactosidase, is produced in the brush border cells of the microvilli in the small intestine (Figure 3).

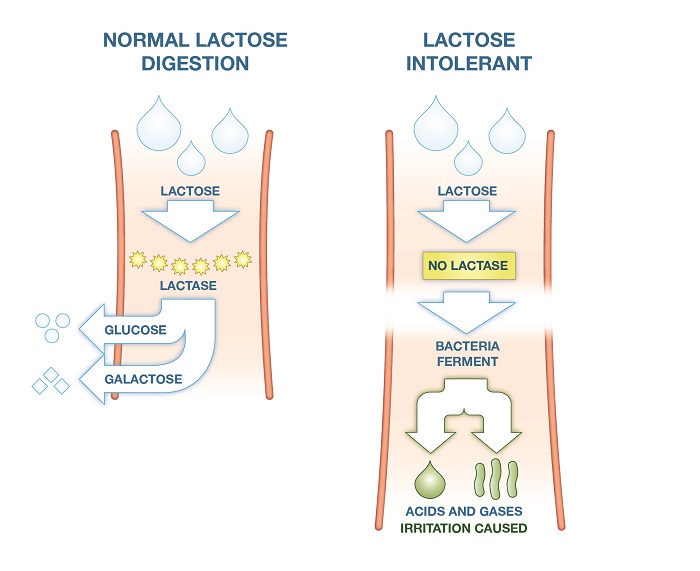

An absence or deficiency of lactase leads to the symptoms of lactose intolerance. The undigested and hence unabsorbed lactose has an osmotic effect on the gut, drawing in water. As it passes into the large intestine the microflora ferments it forming fatty acids and the gases carbon dioxide, hydrogen and methane (Figure 4). Together, these actions result in the classic symptoms of abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea and wind.

Figure 4:

There are two main types of lactose intolerance:

Primary lactose intolerance is the most common form in adults but is rare before one year of age.11 It occurs due to the gradual decline in lactase production following weaning when, naturally, milk consumption is reduced. Technically it is not a medical condition but a normal part of human development; as milk (i.e. lactose) ceases to be consumed, genes for the lactase enzyme are down-regulated ultimately resulting in the inability to digest lactose. Primary lactose intolerance usually presents after infancy as the child matures, normally between five and twenty years of age.12

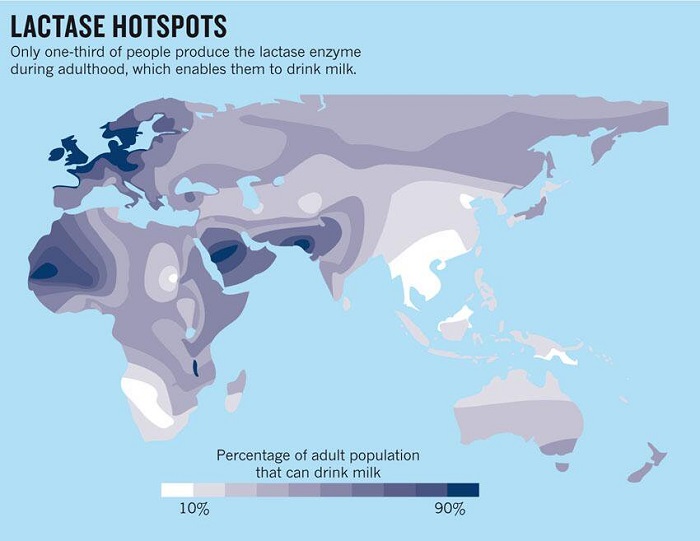

Estimates of the worldwide prevalence of lactose intolerance put it at around 75% of the global population, with some Asian and African populations reaching 100%.

Figure 5: Geographical distribution of lactase production

However, primary lactose intolerance is rare in the UK, affecting an estimated 2% of the population.12 It is likely that the evolutionary advantage of being able to consume dairy when times were hard led to the favourable selection of genotypes that continue to express the lactase gene(s) into adulthood. This selection pressure led to the preservation of lactase production in populations where dairy was available. In cultures where milk was not readily available this evolutionary pressure did not occur and lactose intolerance remains prevalent. Figure 5 shows the geographical distribution of lactose intolerance with the darker areas being hotspots of continued lactase production in adulthood.

Secondary lactose intolerance is the result of gastrointestinal illness, injury to the gut (including surgery) or certain medications, all of which can damage the intestinal mucosa causing loss of lactase-producing cells. Examples of such triggers include coeliac disease, Crohn's disease, gastroenteritis and extensive courses of antibiotics.

It is more common in infants, whose GI tracts are less developed and more susceptible to damage than those of adults. It tends to be a reversible condition with symptoms resolving within months if the gut has chance to recover and lactase production can resume. Acute gastroenteritis is one of the principle causes in infancy and symptoms of lactose intolerance frequently follow such infections, typically lasting for between two and four weeks.

Lactose intolerance can also be due to a genetic abnormality where one or more of the genes required for lactase production are missing or dysfunctional. This is extremely rare and will present early in life with the infant being unable to tolerate milk.