Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage".3

The British Pain Society (BPS) defines chronic pain as "continuous, long term pain of more than 12 weeks or after the time that healing would have been thought to have occurred in pain after trauma or surgery".1

In order to understand how opioids exert their effect it is important to understand how the body experiences and responds to pain.

Pain is detected by specialised receptors called nociceptors. These receptors are distributed throughout the body and are found under the skin surface and on the walls of the internal organs. Nociceptors differ in the stimuli that they detect, some respond to heat, chemicals, or mechanical injury. Once the nociceptor has detected a harmful stimulus it generates a pain signal which is transmitted to the nervous system where the information is interpreted. This process is called nociception.

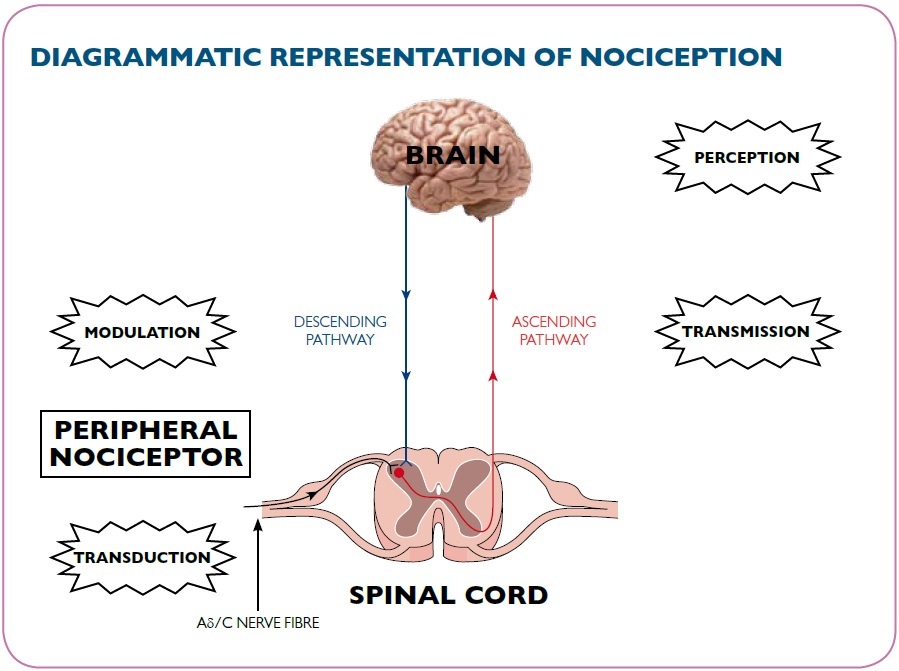

The nociceptive pain pathway consists of four main stages:

- Transduction

- Transmission

- Perception

- Modulation

We will consider each of these stages using the example of a cut finger to illustrate.

Transduction involves the nociceptor identifying the painful stimuli, in this case the finger wound, and converting this information into a pain signal in the afferent nerves. Various neuromodulators are involved in this process including bradykinin and prostaglandins.

Transmission is the process involved in passing the pain signal in the ascending pathways to the central nervous system (CNS). Both the fast myelinated Aδ fibres and the slower unmyelinated C fibres are involved in transmitting the pain message. The Aδ fibres cause the initial sharp stabbing pain whilst the C fibres cause the slower and longer lasting throbbing aching pain. The chemical mediators involved in the transmission of pain include endorphins, glutamate, ATP, and other neuropeptides including substance P. Once the nerve signal reaches the spinal cord, the message is transmitted up to the brainstem and then to the thalamus.

Perception of pain occurs when the thalamus links to the higher brain centres. It is only when the message reaches this level of the CNS and is interpreted as being a pain signal that it actually exists as pain. In our example it is at this stage that the body realises that the finger is cut and it is painful. Perception of pain is a complex process involving emotional, behavioural and sensory factors. It is for this reason that individual perception of pain varies and is commonly referred to as the person's individual "pain threshold".

Modulation is the process where the perception of pain can be increased or decreased. Modulation can occur either within the spinal cord or within the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The spinal cord has a series of mechanisms that can modify the pain message between transmission and perception including the 'descending pathway'. Descending pathways are neuronal pathways that descend from the central nervous system and act to reduce the pain signals that are travelling up the ascending pathways from the body to the brain.

A good example of a modulating mechanism is the endorphin system; the body's own painkiller. Endorphins bind to opioid receptors (see below) and activate modulating pathways in the spinal cord. This prevents the release of neurotransmitters thereby reducing the intensity of or inhibiting the transmission of pain impulses to the brain.

Pain can also originate by mechanisms that do not involve nociceptors; this is typically pain that arises as a consequence of continuing or previous damage to nerves. Neuropathic pain, such as trigeminal neuralgia and post-herpetic neuralgia, is outside the scope of this module as it is not alleviated by opioids.