Metabolic syndrome and the link to skin diseases

In OTC

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Patients with inflammatory skin diseases should be targeted and provided with heart health checks by community pharmacy teams

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

• Explain metabolicsyndrome and its relationship with several common skin conditions

• Identify patients at risk of metabolic syndrome

• Appreciate the importance of screening for modifiable CVD risk factors in patients with inflammatory skin disease

The concept of specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) first arose after the Framingham heart study in 1957 revealed how cigarette smoking, high blood pressure and cholesterol levels were all linked to the development of CVD. Since 1957 several other factors have been implicated in causing CVD including family history, age, gender and a sedentary lifestyle. However, it wasn’t until 1988 that clinicians fully appreciated the impact the presence of multiple risk factors had on CVD risk.

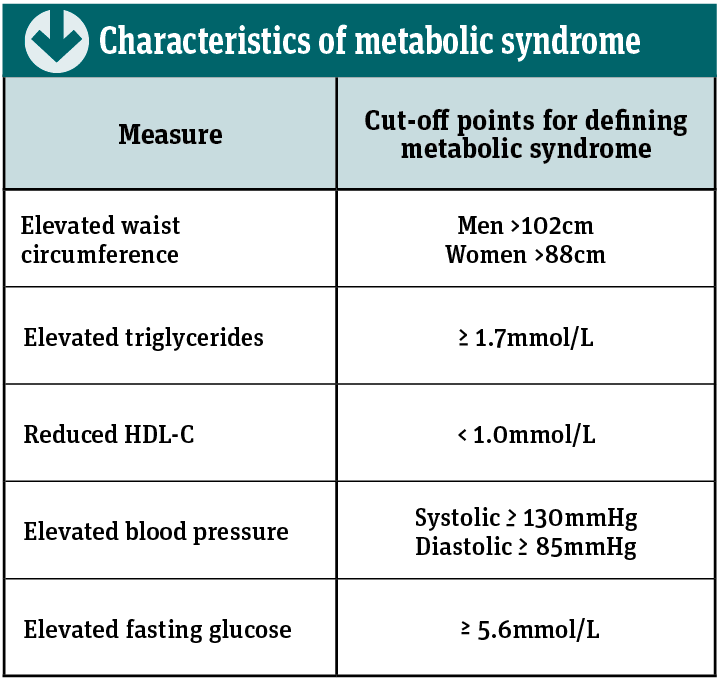

One particular combination found to increase the risk of CVD is elevated triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), central obesity, hypertension and a raised fasting blood glucose level. This collection of risk factors was originally termed ‘Syndrome X’ but has become known as metabolic syndrome.

In the UK, CVD has become a major public health concern with approximately 7.4 million people living with the disease. Emerging evidence suggests that metabolic syndrome is related to a low-grade inflammation in the body, so one group of patients at an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome (and ultimately CVD) are those with inflammatory skin diseases.

Current CVD risk calculators such as Qrisk do not include inflammatory skin conditions in their calculations – so a potentially large number of at-risk patients are not being assessed.

Prevalence and causes

Metabolic syndrome is thought to affect one in three adults aged 50 years or older in this country. Several studies have shown that the presence of metabolic syndrome increases CVD risk. For example, one meta-analysis of 87 studies involving over 950,000 patients found that metabolic syndrome more than doubled the risk of both CVD and strokes, and that risk of all-cause mortality was one-and-a-half times greater.

While the criteria used to define metabolic syndrome have evolved over the years, it is currently diagnosed when at least three or more of the factors shown in the table on p24 are present in an individual.

The underlying cause of metabolic syndrome is not completely understood but is thought to be related to the presence of insulin resistance. Under normal physiological conditions, insulin plays several important roles including:

- Involvement in the uptake of glucose into skeletal muscle and adipocyte (fat) cells

- Promotion of glycogen synthesis in both skeletal muscles and the liver

- Suppression of lipolysis and enhanced lipid storage in adipocytes.

Insulin resistance is characterised by an impaired sensitivity to the effects of insulin, which leads to a reduced uptake of glucose by skeletal muscle cells and an increased release of free fatty acids from adipocytes into the blood.

The higher levels of blood glucose prompt the pancreas to secrete further insulin (because muscle cells are unresponsive), leading to hyperinsulinaemia. In the longer-term, insulin resistance can lead to dyslipidaemia, endothelial dysfunction and chronic hyperglycaemia, all of which contribute towards cardiovascular disease.

One underlying and important contributing factor to the development of insulin resistance is obesity, especially visceral obesity. Visceral fat is no longer viewed purely as an inert fat store as evidence indicates the adipocytes are active cells that secrete a range of bioactive compounds termed adipokines (which are cytokines) that can have either pro- or anti-inflammatory effects in the body.

In the presence of insulin resistance, adipose tissue produces a wide range of pro-inflammatory adipokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a ). In addition, insulin resistance leads to higher levels of specific T cells in the blood and in particular T-helper 1, T-helper 2 and T-helper 17 cells. In turn, these T cells also secrete a number of different cytokines that have been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

The increased level of pro-inflammatory cytokines results in what has been described as a continuous low-grade inflammation in those with metabolic syndrome. In addition, this low-grade inflammation is a key feature of many inflammatory skin diseases and helps account for the increased risk of metabolic syndrome (and ultimately CVD) among those with the conditions discussed below.

Psoriasis

Originally considered purely as a skin disease, psoriasis is now viewed as a systemic inflammatory disease. Although the precise aetiology of psoriasis remains unclear, studies show that patients with the condition have elevated levels of some of the cytokines seen in metabolic syndrome in both their blood and psoriatic plaques. Consequently, much work has focused on drawing parallels between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome.

In one analysis of nearly 400,000 patients, there was a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the 6,868 who had psoriasis compared to those without the disease (28.3 vs 15.1 per cent).

Another study of approximately 1.5 million patients (of which 46,714 had psoriasis) found that those with severe disease were nearly twice as likely as controls to have metabolic syndrome. However, there was also an approximately 20 per cent increased risk of metabolic syndrome even in those with mild psoriasis.

Other research has shown that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of diabetes, which is a component of metabolic syndrome.

Several studies have clearly shown that the presence of metabolic syndrome increases CVD risk

Acne

There is little direct evidence that acne is associated with the metabolic syndrome, although one small study of 85 patients treated for metabolic syndrome found that severe acne was present in 52. However, acne does appear to be associated with insulin resistance, which is thought to be the underlying cause of metabolic syndrome.

For instance, women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have both insulin resistance and acne, while insulin resistance was found to be higher (17 vs 9 per cent) in one study of 100 adult males with acne.

In a further study of 243 patients with severe acne, fasting insulin levels were significantly higher than in controls, indicating the presence of insulin resistance.

Another factor identified in patients with acne is increased mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signalling. The mTORC1 kinase is a nutrient sensing protein, which controls protein synthesis. Increased mTORC1 activity is known to be a feature of insulin resistance, obesity and type 2 diabetes, and has been detected in lesional skin among those with acne.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

A severe and progressive inflammatory disorder of the hair follicles (also known as acne inversa), hidradenitis suppurativa presents with both painful and recurrent nodules, abscesses and sinus tracts, and is diagnosed on the basis of the clinical features. It typically affects the apocrine gland-rich areas including the armpits, anogenital and inframammary areas.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in hidradenitis suppurativa in one study was found to be 50.6 per cent compared to 30.2 per cent in controls and the condition is known to be associated with abnormal levels of several inflammatory cytokines.

Key facts

• Metabolic syndrome is thought to affect one in three adults aged 50 years or older in the UK

• One group of patients at an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome are those with inflammatory skin diseases

• Patients with psoriasis have elevated levels of some of the cytokines seen in metabolic syndrome

Atopic eczema

The fundamental defect in atopic eczema (AE) is epidermal barrier dysfunction and, although the association between metabolic syndrome and AE is less clear, levels of various pro-inflammatory cytokines have been shown to be elevated in AE. In one recent cross-sectional analysis of 116,816 patients with AE, it was found that metabolic syndrome was present in 17 per cent of those with moderate to severe AE. The analysis also found that there was also a higher incidence of the individual components of metabolic syndrome (i.e. diabetes, obesity, dyslipidaemia and hypertension) in patients with moderate-to-severe AE.

Although the available evidence is limited it does appear that metabolic syndrome is also associated with both androgenic alopecia and acanthosis nigricans (which causes darkened, thickened patches in the armpits, neck and groin). In fact, acanthosis nigricans occurs in as many as 74 per cent of people with obesity and diabetes, which are components of metabolic syndrome.

How pharmacy teams can help

With metabolic syndrome a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, community pharmacies can provide health checks for a range of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, elevated cholesterol and hypertension. Given the association between metabolic syndrome and its components such as diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia with inflammatory skin diseases, patients with these conditions should be proactively targeted and screened for traditional CVD risk factors.

Since it is known that lifestyle modification can reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome, pharmacy teams should offer appropriate advice to help reduce CVD risk in those with inflammatory skin diseases.

Focus on... Cetraben

The Cetraben line-up is described as a range of “specialist moisturisers for dry skin conditions such as eczema, flaky skin, itchy skin, psoriasis and dermatitis”. The range comprises a daily cleansing cream, an overnight ointment for dry, eczema-prone skin and flare-ups, a bath additive and a 2-in-1 daily cleansing cream. Latest addition to the range is a natural oatmeal cream. The range is accredited by the British Skin Foundation.

Skin rashes and Covid-19

Data collected as part of the coronavirus symptom app study by a team from King’s College London has suggested that skin rashes should be added to the list of common Covid-19 symptoms

Patient data has shown that skin rashes can occur in conjunction with the other classic Covid-19 symptoms. For example, according to information gathered by the King’s College team, 47 per cent of patients reported that a skin rash appeared at the same time as other Covid-19 symptoms, after the onset of symptoms (35 per cent) and prior to the onset of symptoms (17 per cent). In 21 per cent of those testing positive for Covid-19, the rash was the only symptom.

Although this is a rapidly evolving area, some of the skin changes reported in case studies are listed below:

Petechial rashes

These consist of small non-blanching lesions, although case reports suggest that this type of rash occurs in patients who are systemically unwell and during acute infection.

Pseudo-chilblain

This appears to be a more popular presentation among those with Covid-19 based on 304 published cases. The condition most commonly affects the toes (see picture) but is also seen on the fingers. The condition can be asymptomatic but reported symptoms have included itch and tenderness and sometimes occurs after oedema. These lesions have been commonly reported in children and adolescents who are mildly symptomatic and can develop within days of infection, although the evidence linking these chilblains with Covid-19 is limited.

Vesicular eruption

A vesicular rash consisting of small and pruritic blisters (which are less than 5mm in size) has been identified in several reports. The rash itself can be localised to the sub-mammary region or even generalised to the whole body. It seems that patients develop the rash at the onset of symptoms and it can take up to 10 days to resolve.

Urticarial rash

A classic urticarial rash has been observed in some patients affecting either the face, trunk or limbs and there is one case associated with angio-oedema. In general the urticaria lasted for between two and nine days and was managed with regular antihistamines. However, since urticaria is known to be associated with both infections and drugs, it might not be due to Covid-19.

Mucocutaneous

Lesions occurring in the mouth, eyes and genitals have also been described in five cases that have been thought to be due to infection with the virus.

Other rashes include a maculopapular rash and erythema multiforme, although patients were also prescribed medicines which may have been responsible. Overall, it seems that patients can develop skin rashes when infected with Covid-19 but there is a limited amount of data available to clearly define an association between the rash and infection with the virus. Until more is known, pharmacy teams should remain vigilant for any patient who seeks advice for any of the above skin conditions.