In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you will:

- Understand what malnutrition is

- Appreciate that increasing age and certain medical conditions can predispose an individual to malnutrition

- Be able to identify malnutrition.

Introduction

At any point in time, more than 3 million people in the UK are at risk of malnutrition. Most (around 93 per cent) live in the community1. Those over 65 years old and people with long-term conditions are particularly at risk2.

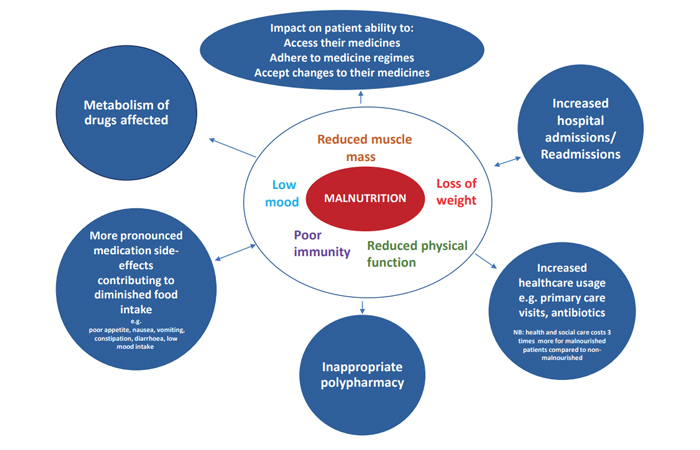

Increasing age and multi-morbidities also result in the need for multiple medications, so individuals at risk of malnutrition will frequently come into contact with pharmacy teams.

As part of their role in evaluating the ongoing effectiveness of medications, pharmacists are increasingly expected to understand the role of nutrition and hydration in malnutrition and to review the use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS) to ensure they are both clinically and cost-effective.

The NICE Quality Standard for Nutrition Support in Adults,QS243 requires that all care services take responsibility for the identification of people at risk of malnutrition and provide nutrition support for everyone who needs it.

The clinical consequences of malnutrition include:4

- Impaired immune response

- Reduced muscle strength

- Frailty

- Impaired wound healing

- Increased risk of falls

- Impaired recovery from illness and surgery

- Impaired psycho-social function

- Poorer clinical outcomes (e.g. higher mortality, poorer quality of life).

Identifying malnutrition

As key members of the community healthcare team, pharmacists are in an excellent position to identify those at potential risk of malnutrition, offer first-line advice or activate patient support. To help identify those at risk, Table 1(below) outlines the type of individuals who are at risk and explains the reasons why.

Assessing those at risk

Where malnutrition risk is being considered, there should be a process of:

- Information gathering

- Interpretation

- Informed decision-making.

These do not have to happen at the same time and can be done by different care professionals. The important thing is that the observations are being noted, actioned and the patient is getting the help they need. So how might this information be gathered in pharmacy practice?

| Table 1: Individuals at risk of malnutrition and factors contributing to its development | |

| Patient group | Reasons why malnutrition can develop |

| Frail old person |

Eating and drinking can become more difficult due to physical challenges affecting the ability to cook, chew, swallow food, use cutlery, or see food and drink Reduced muscle strength increases the risk of falls and injury, further increasing the likelihood of malnutrition secondary to a reduced ability to care for themselves and lower nutritional intake during and after hospital admission |

|

Those with dysphagia (impaired swallowing) |

Texture modified diets (e.g. pureed food) may be less appealing and of lower nutrient density unless fortified or supported with oral nutritional supplements of the right thickness. Swallowing difficulties may also induce fear of eating associated with the risk of choking and so further impairing food intake |

|

Recent hospital admission for medical |

Unfamiliar environment and foods can reduce intake. Intake may be interrupted, including in nil by mouth situations, for investigations and surgical interventions. The catabolic effect of injury or illness also reduces appetite and the desire to eat, and can persist for several weeks after discharge |

|

Chronic disease (e.g. COPD, gastrointestinal disease [e.g. IBD], cancer) |

Acute episodes and exacerbations may increase nutritional requirements. The condition itself or the side-effects of treatment can alter taste and affect appetite, digestion and absorption |

|

Social issues, mood |

Poor support, low mood or being housebound can affect motivation and ability to obtain and take medicines and/or food |

|

Progressive neurological disease (e.g. dementia, Parkinson’s, stroke, motor neurone disease) |

As physical strength and co-ordination declines, this can make sourcing and preparing food, as well as eating and drinking, more difficult |

Nutritional status

Nutritional status can be explored both objectively and subjectively. Pharmacists may be used to asking about weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI) for therapy dosing or general health checks. Knowing a patient’s weight, weight history and height can also be helpful in using a validated tool to screen for malnutrition. Current weight and height will allow BMI* to be calculated and documented.

Comparison of current weight with weight three/six months ago will identify weight loss.

The British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition MUST self-screening tool can be used by professionals, patients and carers (malnutritionselfscreening.org/self-screening.html).

NOTE: While BMI is an indicator of malnutrition, excess body weight does not guarantee protection from the disease-related condition. As two-thirds of the population are now overweight or obese, it is important that unexplained weight loss and impaired [nutritional] intake are recognised as potential markers of malnutrition.

Subjective assessment can also be helpful in identifying the risk or likelihood of malnutrition and can facilitate an exploration of the reasons why it might be developing, which then informs potential management or risk reduction.

Questions to a patient that might help guide conversations regarding nutrition include:

- Has your appetite changed?

- Have you noticed you are eating less at a mealtime?

- Do you miss any meals?

- Who prepares your meals?

- Who do you eat with?

- Has your weight changed and, if so, by how much?

- Does any change in weight affect medicines prescribed or the dose?

If the current weight is not known, there are a number of subjective indicators of malnutrition risk that pharmacy teams can look out for. These include:

- Thin or very thin appearance

- Asking for liquid medications due to feeding or swallowing difficulties

- Dry skin, skin becoming looser and breaking more easily

- Changes in bowel habit

- Needing more sleep or rest

- Reduced functional ability.

| Table 2: Examples of nutritional symptoms and considerations | ||

| Problem/symptom | Considerations | Resources |

| Early satiety, reduced appetite, feeling full after small food amounts |

Offer advice on eating nutrient dense foods (foods high in protein, energy, vitamins and minerals). Promote ‘little and often’ |

Information sheets for patients on how to deal with common symptoms that may interfere with their ability to eat and drink can be found here. |

|

Dysphagia |

Consider the need to refer to GP/speech and language therapist/dietitian |

|

|

Dry mouth, sore mouth, fatigue, chewing difficulties |

Assess if issues are caused by external factors such as poor dentition or oral thrush [pharmacists can give |

|

|

Altered bowel habit, vomiting |

Check for causes: disease, side-effects of medicines/treatment, infection. Consider referral to GP or dietitian |

|

|

Anxiety/depression |

Consider referral to appropriate professional |

|

|

Social issues |

Is help required with activities such as shopping and cooking? Consider referral to social prescriber, social services, meals on wheels |

|

|

If patients have a medical condition that necessitates a special diet, such as diabetes or kidney disease, advice and guidance may need to be sought from a dietitian or specialist nurse. |

||

Medication

Medicines can contribute to the causes of malnutrition but may also be a potential solution. For example, some medicines might cause side-effects that interfere with appetite and so may need adjusting, while others might be needed to alleviate various symptoms that affect eating and drinking (e.g. an anti-emetic for nausea/vomiting).

Table 2 (above) summarises common problems that can interfere with food intake along with actions that can be taken by members of the healthcare team including pharmacists to address them.

In part two next month, we will look at managing malnutrition according to risk category and consider how optimal nutritional intake can be managed.

References

- Elia M and Russell CA. Combating Malnutrition: Recommendations for Action. Report from the Advisory Group

on Malnutrition, led by BAPEN. 2009 - Stratton R, Smith T, Gabe S. Managing malnutrition to improve lives and save money. Redditch: British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2018.

- National Institute for of Health and Care Clinical Excellence (NICE). Nutrition support in adults. Quality Standard 24. 2012.

- Holdoway A et al. Managing Adult Malnutrition in the Community. 2021.

- The ‘MUST’ report. Nutritional screening for adults: a multidisciplinary respo