Why all the fuss about biosimilars?

In OTC

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Biosimilars have been exciting attention in secondary care for over a decade but seem to have made little impact in the community. This is mainly down to the conditions they are used to treat and the way they are administered – but it won’t always be that way

Key facts

• Biosimilars are developed to be clinically equivalent to an existing biological drug

• They offer the NHS the potential for significant savings

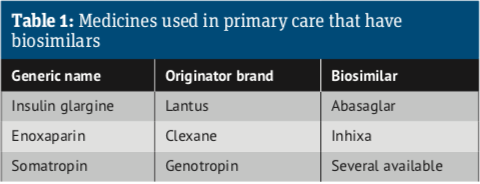

• Insulin glargine was the first medicine managed in primary care to have a biosimilar

• There are a number of barriers to implementing biosimilar use

Biological medicines, including biosimilars, are complex protein-based treatments made or derived from living organisms, typically using recombinant DNA technology. Biologics can be tailor-made so that they bind to specific targets in the body. Typically, they are used to treat long-term and complex conditions such as cancers, rheumatoid biosimilars for the original product. Due to their complexity, biosimilars take longer to develop and are considerably more expensive to manufacture than conventional generics. The regulatory approval process is also fundamentally different.

Generics require limited clinical development but, in the case of biosimilars, the European arthritis, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease and growth disorders. “Substitution is not permitted for biological medicines” Commission issues specific guidelines for each product which specify the procedures, including appropriate clinical trials, Biosimilars are developed to be highly similar and clinically equivalent to an existing biological medicine. Like generics they are marketed after the expiry of the patent on the originator or reference product and, like generics, they can offer considerable cost savings to health providers.

Unlike generics there can be no inter- changeability or automatic substitution of to be performed in seeking regulatory approval. A biosimilar does not need to demonstrate safety and efficacy in each indication as this is done by reference to the originator product that has already satisfied these requirements. In a similar vein, where NICE has already recommended the originator biologic, the same guidance will apply to its biosimilar.

Since biosimilars are therapeutically equivalent to their reference product, a prescriber can switch a patient from the reference biological medicine to its biosimilar. However, since biosimilars are not identical, MHRA guidelines require all biological medicines to be prescribed by their brand name and not by their international non-proprietary (generic) name. This means pharmacies need to bear in mind that substitution is not permitted for biological medicines, including biosimilars.

Substitution is not permitted for biological medicines

Biosimilars – What are they?

The European Medicines Agency defines a biosimilar as a biological medicinal product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorised original biological medicinal product (reference medicinal product). A biosimilar demonstrates similarity to the reference product in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety and efficacy based on a comprehensive comparability exercise.

How long have they been around?

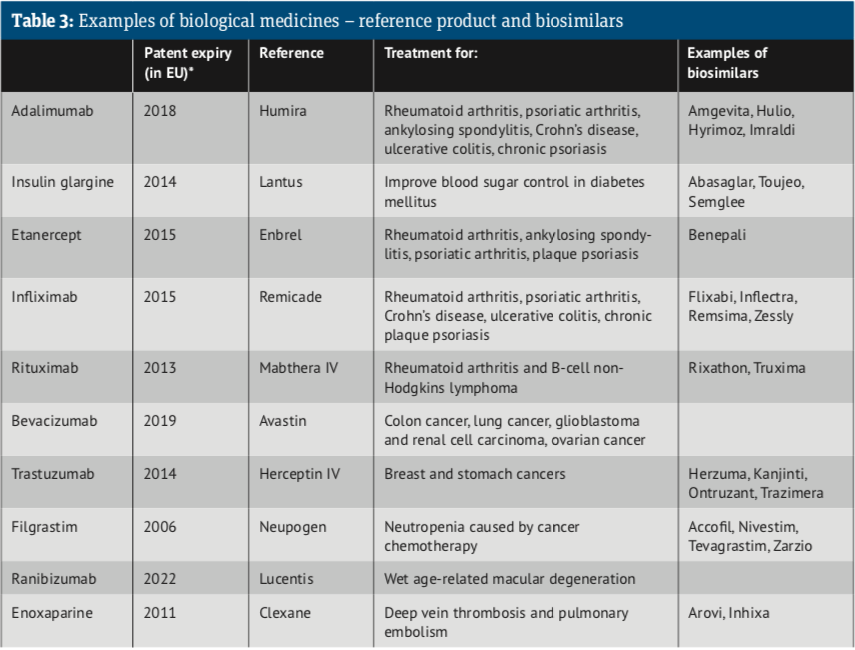

The first biosimilar, Omnitrope, a somatropin biosimilar to Genotropin, was approved in 2006. By November 2018, biosimilars to 15 reference medicines (35 biosimilar molecules marketed as 53 brands) had been authorised for use by patients across Europe. The list has since grown to around 70 brands. The latest information can be found on the EMA website.

Since 2013, the European Commission, on the advice of the European Medicines Agency, has authorised biosimilars for infliximab, etanercept, rituximab, adalimumab, trastuzumab, bevacizumab, enoxaparin, insulin glargine, insulin lispro, teriparatide, follitropin alfa and pegfilgrastim, to add to those already approved: somatropin, filgrastim and epoetin alfa. Take a look at the Biosimilar medicine guide.

An eye to cost...

Biological medicines are the largest cost and cost growth area in the NHS medicines budget. While the NHS has been alert to the potential for significant savings as biologics come off patent, biosimilars are more challenging and expensive to develop than generic medicines, so do not offer the same dramatic price reductions.

Savings to the NHS in England of at least £200m-£300m a year by 2020/21 were possible, according to NHS England’s Commissioning Framework for Biological Medicines when it was published back in 2017.1

The framework set a target of getting at least 90 per cent of new patients onto the best value biologic within three months of the launch of a biosimilar and at least 80 per cent of existing patients within 12 months.

Since 2016 there have been secondary care introductions of biosimilars of etanercept, infliximab, rituximab, trastuzumab and adalimumab across the UK.

In September 2018 Richard Seal, the regional pharmacist for Midlands and East of England for NHSE&I, highlighted a reduction in spend for three of these high cost biologics (infliximab, etanercept and rituximab) from £41m a month in 2015 to £24m in 2018. During the period the total volume of product used increased from 14.5kg to 16.8kg/month.2

In November 2018 the NHS announced it was set to save £300m annually, or around 75 per cent, after negotiating deals with five manufacturers of biosimilars of Humira (adalimumab).

An indication of the uptake of biosimilars in secondary care can be seen in figures published in March this year from the London Procurement Partnership. They showed that in February 2019, in London, 87 per cent of etanercept, 94 per cent of infliximab, 92 per cent of rituximab and 95 per cent of trastuzumab was dispensed as a biosimilar.3

Primary care running slow?

Insulin glargine (Lantus) was the first medicine managed in primary care to have a biosimilar, with Abasaglar launched in the UK in September 2015. However, the uptake of biosimilar insulins has been slow, generating savings of only £900,000 between October 2015 and December 2018.

The ‘missed savings’ amounted to £25.6m in this period, indicating that only 3.42 per cent of the potential savings were achieved.4

The total prescribing for insulins in primary care across all CCGs in England was approximately £327m from March 2018 to February 2019, of which £72m was insulin glargine, according to a March 2019 report from NHS Commissioning Support Units on ‘Primary Care Biosimilars – Insulin’.5

Only 7.7 per cent of the spend on insulin glargine prefilled pens and cartridges was for the biosimilar brands. Switching patients’ therapy to biosimilar insulin products could yield savings across England of between £1.7m-£7.5m over a 12-month period, the report said.

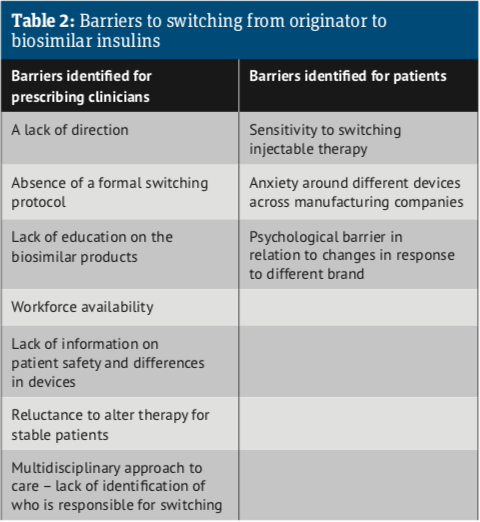

The report went on to identify a number of barriers to implementing the use of biosimilar products (see Table 2). A lack of direction and the absence of formal switching protocols is holding back a switch to biosimilars. Education of pharmacists, GPs and patients is also an issue.

While the uptake and use of biosimilars in secondary care is well-established there is still some way to go in primary care, both in terms of the biologics that can be regularly prescribed by GPs, and in knowledge and understanding of their uses and benefits. But it won’t always be that way.

Note that patent expiry dates for biological medicines in Europe and the US often differ.

Useful resources

• What is a Biosimilar Medicine?

• European Medicines Agency: Biosimilar medicines – overview

• Specialist Pharmacy Service: Is it safe to switch to a biosimilar?

• Commissioning Framework for Biological Medicines (including biosimilars) 2017

• Guideline for the managed introduction of biosimilar basal insulin.

References

- Commissioning framework for biological medicines

- Webinar Sept 2018

- London Procurement Partnership. Uptake of Biosimilar Etanercept, Rituximab, Trastuzumab and Adalimumab in London (Feb 2019)

- Real-World Budget Impact of the Adoption of Insulin Glargine Biosimilars in Primary Care in England (2015-2018) Diabetes Care 2020 Jun

- Report of Findings: Primary Care Biosimilars – Insulin