Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Clinical

Follow this topic

When conceiving is a problem

In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Having some insight into assisted conception can transform any interaction when counselling women who are undergoing fertility treatment

Infertility is estimated to affect around one in seven heterosexual couples in the UK. There are many causes – ovulatory disorders, tubal damage, sperm problems, uterine or peritoneal issues, pelvic conditions such as endometriosis, gamete or embryo defects – but in around a quarter of cases, the origin is never identified.

Appropriate investigations (for example, ovulation testing, uterine and tubal checks, semen analysis and screening for infections) are key in determining whether treatment should be medical or surgical to restore fertility, or if assisted reproductive techniques (ART) are the next step.

Assisted conception

Availability of and eligibility for NHS fertility treatment varies across the UK. Anyone looking to privately fund treatments should be encouraged to choose a clinic licensed by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

Fertility drugs may be all that is needed, or may be combined with ART as detailed below.

The main medicines used are typically as follows:

• Ovulatory stimulants such as clomifene, metformin, gonadotrophins (e.g. cetrorelix) and dopamine agonists (e.g. cabergoline)

• Gonadorelin analogues such as nafarelin may be used to suppress the normal menstrual cycle before ovulatory stimulants are used

• Gonadotrophins may be prescribed to men to stimulate sperm production.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) involves inserting selected sperm from a previously gathered sample into the uterus, sometimes after the woman has undergone ovarian stimulation. It may be the most appropriate technique for couples who can’t have vaginal sex, perhaps because of a physical disability, or if unprotected sex is inadvisable; for example, because one partner has HIV.

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) starts with the woman medically suppressing her normal menstrual cycle, before undergoing ovarian stimulation. Eggs are removed and fertilised with selected sperm in a laboratory, then one or two of the resulting embryos are returned to the uterus to hopefully implant and develop as in a naturally conceived pregnancy.

Surgical sperm extraction may be performed on men who have little or no sperm in their semen, maybe because of a vasectomy, cancer treatment or previous infection, or who cannot ejaculate.

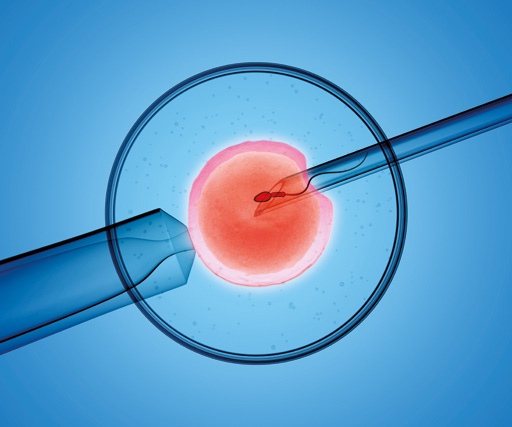

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is an option if infertility is sperm-related, as it consists of injecting the sperm directly into the egg before the resulting embryo is returned to the uterus.

Egg and/or sperm donation is sometimes used if one partner has been identified as having a problem that is making conception unlikely. Donated sperm is used from IUI and donated eggs via IVF. Since 2005, anyone who has registered to donate eggs or sperm is required to provide information about their identity, as any children born as a result has a legal entitlement to know their parentage when they turn 18 years of age.

Useful advice

Pointers to bear in mind when dealing with patients undergoing fertility treatment:

- Emotions and stress levels are often high, partly because the couple is likely to have experienced many disappointments before accessing fertility services, but also because treatment cycles are limited due to NHS funding restrictions or the pressure of paying on a private basis. Pregnancy testing is a particularly fraught time, with women dreading a negative result yet fearing the continuing anxiety that may accompany a positive outcome due to the increased chance of a multiple – and therefore high-risk – pregnancy and birth. Be reassuring, supportive and kind.

- Don’t overlook men. They may feel under a great deal of pressure, both personally and in terms of supporting their partner as she undergoes what may be invasive treatments, frequently with the added internal stress of having to be “the strong one”.

- Treatments can be costly, so don’t be judgemental if someone asks for a private prescription price but then goes elsewhere.

- Be aware that some medicines are used outside their licences: metformin, for example, may be used to reduce the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, and sildenafil is sometimes used to help thicken the endometrium and make a more hospitable environment for the embryo. Ask the patient if a prescription seems unusual, rather than assuming a prescribing error has been made and automatically moving to resolve the issue.

- Appreciate the difference between what are the normal side-effects of a drug and what may be signs of a miscarriage. For example, light vaginal bleeding after embryo transfer can indicate implantation but heavier bleeding and periodlike pains suggest something has gone awry. Also be on the look-out for anything that may suggest an ectopic pregnancy, such as pain in the tip of the shoulder and sudden abdominal discomfort, and refer urgently.

- Understand guidelines around sexual intercourse. For instance, a man who is providing a sperm sample is likely to be told to not ejaculate for anything between two and seven days before his appointment, and women who have undergone embryo transfer may be told to abstain from sex for a couple of weeks (until after pregnancy testing) or sometimes longer.

- Remember the usual advice regarding pre-conception care and early pregnancy – e.g. getting to and maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding alcohol, caffeine and smoking, and folic acid supplementation. Be respectful of any choices couples may make regarding ways to improve fertility. There may not be a convincing evidence base for many of these but let it go if it isn’t harmful.

- When recommending OTC medicines be aware that your PMR system may not provide a full picture. Ask to see a treatment booklet and check interactions using the BNF and the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS).

- Signpost to credible sources of information, such as the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), the NHS website and Best Use of Medicines in Pregnancy (BUMPS). Much of the material on the internet is anecdotal at best, and misleading and potentially harmful at worst.

• Thanks to Mona Koshkouei, clinical standards manager at McKesson UK, for her help in putting together this article.

More information

• The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority

• NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary (CKS) on infertility (updated in April)

• Reliable information on drugs during pregnancy is available from UKTIS with the related BUMPS site for patients

• Medicines Complete hosts the BNF

• The main NICE clinical guideline on assisted conception. NICE has also published a quality standard on infertility

• Patient organisations that may be helpful include Fertility Fairness , Fertility Network UK, the Pituitary Foundation and the British Infertility Counselling Association